CYPRES in Space

Tuesday, April 3, 2018

- Team CYPRES

- 4/03/18

- 0

- Aad Technology, Custom Solutions, General

CYPRES Cutters Are Going On The World’s First Amateur Manned Space Mission

Possibility is a funny thing. If it’s not impossible for someone to be knocked unconscious when they jump out of a plane and wake up uninjured in a field below, is anything truly impossible?

There’s a spaceship being built by a group of around 60 amateur space enthusiasts in Denmark that says it’s not.

Fittingly enough, there are CYPRES components on that ship. They’re there because skydiver and financial professional Mads Stenfatt is one of the craft’s potential pilots when it makes its maiden voyage. Since he’s in charge of the rockets’ parachutes, he made sure that CYPRES would be along for the ride…but more on Mads later. First, we need to tell you all about this riveting human endeavor.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

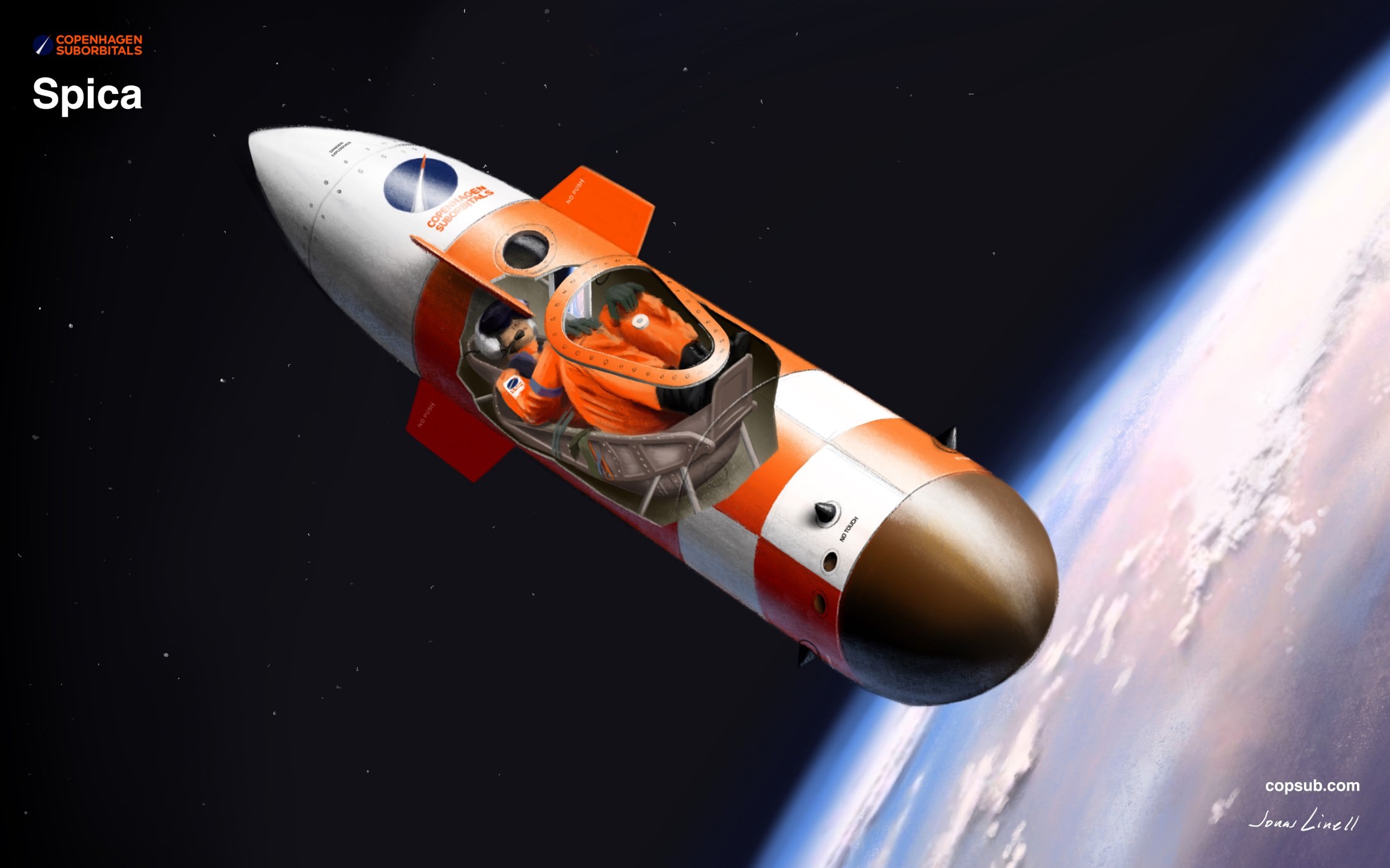

The spacecraft in question is being built by the world’s one-and-only manned, amateur space program: Copenhagen Suborbitals, founded in 2008. The mission’s workshop is in Denmark, but the audience–and crowdfunding base–for this homespun, non-profit, open-source, D.I.Y. space endeavor is worldwide.

Copenhagen Suborbitals’ motley coalition, composed entirely of volunteers and drawn from incredibly diverse backgrounds, is entirely amateur when it comes to space. Indeed, the team builds spacegoing rockets in the off time from their day jobs. These herculean efforts square up to one simple end goal: To fly one amateur astronaut over the Kármán Line (space’s official border, which sits at 100 kilometers above the Earth’s surface). From there, the capsule will freefall straight back down and land–by parachute, naturally–in the sea.

So far, progress is strong. Since 2011, the program has already built and flown five unmanned rockets and space capsules. Their last rocket went up in 2016, and the team is ready to launch a follow-up this year.

Even considering the deceptive simplicity of the goal, the list of challenges stretches out and out.

First, there’s the budget. Even though people all over the world contribute funds to pay the project’s materials, tools and rent, the project’s total budget sits in the thousands as opposed to the billions. (The team recently did a back-of-the-envelope calculation that estimated the mission’s budget at about 10% of NASA’s budget for–well–coffee.) Copenhagen Suborbitals, after all, enjoys no government or corporate funding. However, the team cheerfully makes do, innovating ways to create complex systems from inexpensive, readily available materials. The workshop uses low-technology production methods and studiously avoids expensive, exotic materials to achieve its ends. Furthermore, project participants cover all their own expenses, not using donation funds for even so much as a snack. The sponsor team–of which CYPRES is proud to be a part–provides donated materials and discounted components. (Notably, these contributions are done without expectation of weight in project decision-making.)

Secondly, there’s the fact that getting the appropriate permissions to launch a vehicle into space is virtually impossible. To get around that limitation, Copenhagen Suborbitals launches its rockets from a sailing platform in international waters. (Interesting note: They’re the only spaceflight organization that does that.) The project’s mission base is the seaside town Nexø on the east coast of the Danish island of Bornholm, affectionately referred to as “Spaceport Nexø” by project participants. The launch site is a platform in the Baltic Sea, 20 kilometers off the Bornholm coast.

Thirdly, there’s the sheer inherent danger and stupefying complexity that the goal represents. The team is working around the steep challenges of spaceflight without the test environments, crew numbers and braintrust that governmental space missions enjoy as a baseline. Mads Stenfatt–the skydiver we mentioned earlier as the reason CYPRES is onboard this mission–is using our components to try to tackle one of the myriad of sticky problems. (Mads’ day job is at the biggest bank in Denmark, working as a pricing analyst with major commercial clients, so he knows his way around sticky problems.)

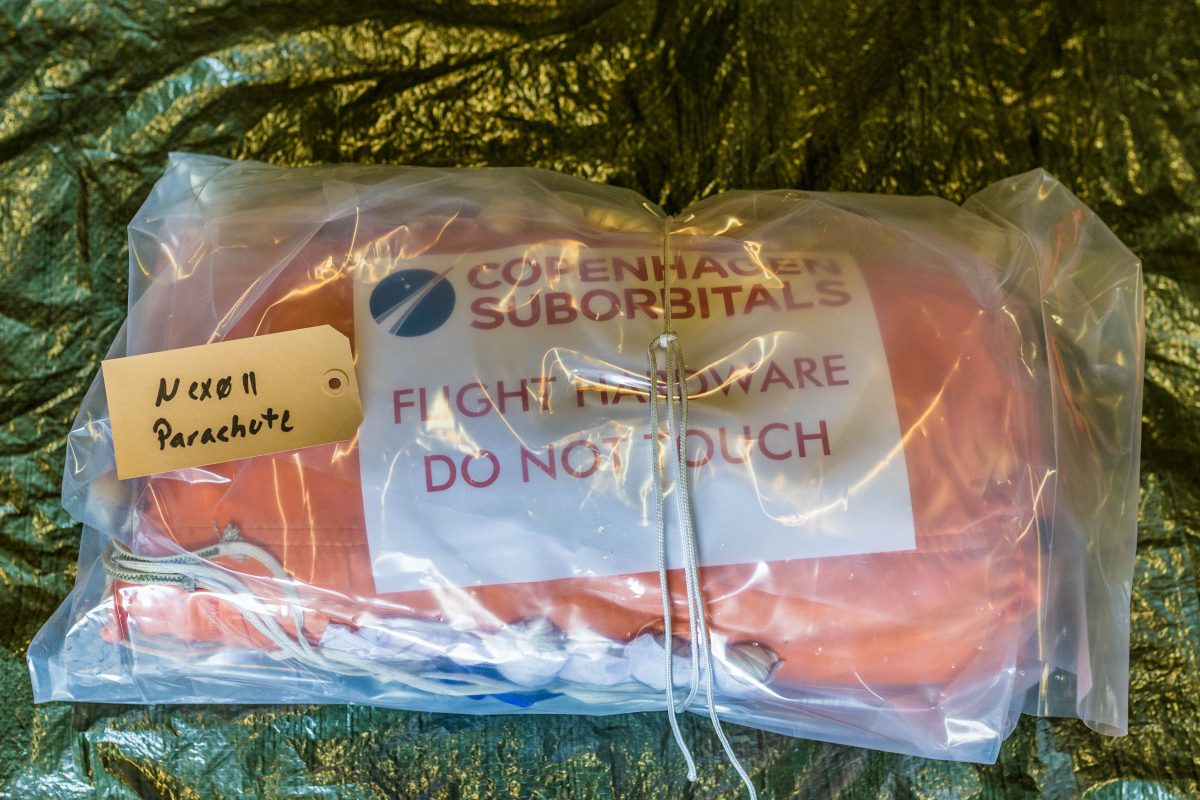

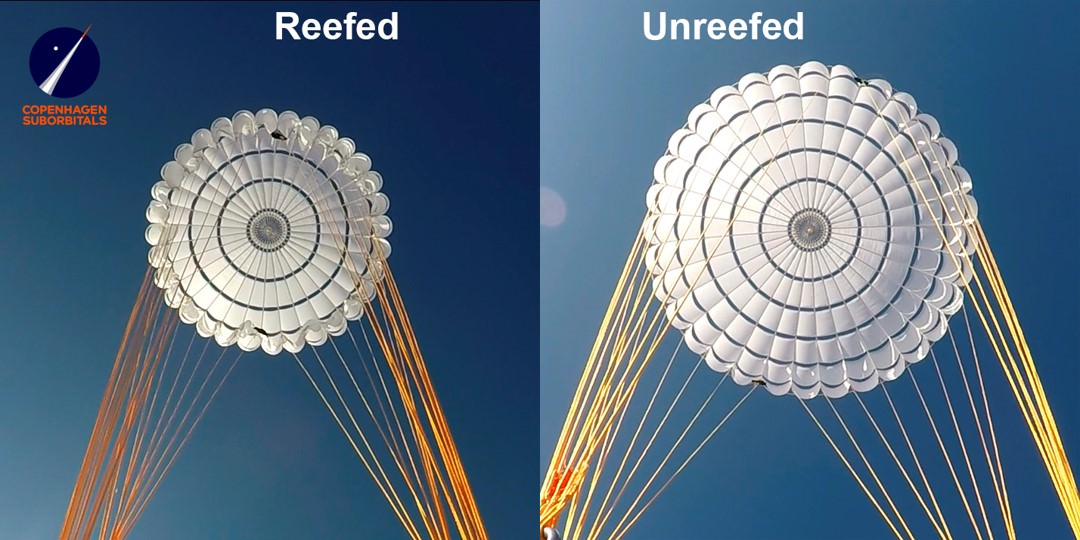

In the current rocket class (called “Nexø”) the mission uses CYPRES cutters in two places: In the reefing system that reduces the parachute’s opening load, and in the system which releases the ballute–which is, basically, a high-speed-tolerant drogue–and drags out the main deployment bag.

Copenhagen Suborbitals’ two existing Nexø rockets are being used to test various systems before building the first Spica-class (in other words, astronaut-ready) rocket, so reliability is key. As most skydivers would have experienced, sliders can behave unpredictably, either staying up longer than intended, or slamming violently down fo a hard opening. For a rocket carrying a human payload, neither of those non-optimal outcomes would be acceptable.

“When it comes to a situation like ours,” Mads notes, “We only see very few parachute openings per year. Therefore, a more technically controlled method to keep the opening sequence under control, that costs a little, is preferred over a ‘free of charge’ method.”

Early in the project, the team tried to test their home-built parachutes with equally home-built sliders. Unfortunately, the resulting reliability was never quite satisfactory for the task at hand.

“When I studied how the big guys solve this problem,” Mads explains, “It became apparent that they used a so-called ‘reefing system,’ typically designed to use various pyrotechnical methods or mechanical devices. We bought and tested a mechanical device, but couldn’t obtain a predictable behaviour, so that method was quickly discarded. Looking into the pyrotechnical method, we could see many advantages, but were unable to build it ourselves or obtain the devices used by the ‘grownups.’”

“Being a skydiver myself,” he continues, “I already rely on the reliability and trustworthiness of my CYPRES AAD. The team then did a brainstorm. If we could design the rest of the system that senses when the parachutes open, couldn’t we then integrate the CYPRES cutter into that? Having come to a positive conclusion on that question, we then had a very enthusiastic and detailed discussion with the Airtec engineers, who explained what it would take to make the cutter activate. Many tests later, we have ended up with a system that incorporates a cutter in each box.”

The team has seen a few failures on the system, but Mads is quick to point out that those errors have always been due to other parts of the setup. Even under these extreme pressures, the CYPRES cutters have worked flawlessly every time they received their signal. We couldn’t be prouder to be a part of Copenhagen Suborbitals’ mighty project–and no one will cheer louder when that first amateur manned space mission arcs over the Kármán Line and lands under three fully inflated parachutes.

The team has seen a few failures on the system, but Mads is quick to point out that those errors have always been due to other parts of the setup. Even under these extreme pressures, the CYPRES cutters have worked flawlessly every time they received their signal. We couldn’t be prouder to be a part of Copenhagen Suborbitals’ mighty project–and no one will cheer louder when that first amateur manned space mission arcs over the Kármán Line and lands under three fully inflated parachutes.

Possibility, after all, is what you make of it.

If you, too, want to see an amateur in space, connect with Copenhagen Suborbitals to show your support:

https://www.facebook.com/CopenhagenSuborbitals/

https://www.instagram.com/copsub/

https://www.youtube.com/user/CphSuborbitals

Adventure, Tips, and Adrenaline

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

By signing up for our newsletter you declare to agree with our privacy policy.