CYPRES Goes to Space — Again!

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

- Team CYPRES

- 3/20/19

- 0

- Aad Technology, Custom Solutions, Cutter, General

What do Starfleet, Battlestar Galactica’s Colonial Fleet and CYPRES have in common? More than one epic trip to space! The cool part: The CYPRES is the only item on that list that happens to be–well–real, and we’re really excited about this next partnership. It seems like yesterday that our cutters were on the Copenhagen Suborbitals space-going vehicle, and now we’re crossing the Kármán line once again with the NABEO dragsail Project of HPS GmbH flying on the Rocket Lab Electron rockets. Rocket Scientist Thomas Sinn sat down to chat with us about what they’re up to. (The author may or may not have worn her Star Trek communicator badge during the interview.)

Rocket science from the very beginning

Thomas Sinn has been infatuated with rockets as long as he can remember. In fact, he says that his earliest childhood memories were located right next to a European rocket engine test site. Once grown, he started studying aerospace engineering at Stuttgart; he continued on to earn a Master’s in the subject at the University of Kansas, close to the (perhaps-surprisingly-cosmopolitan) Kansas City. When he completed that degree in 2010, he bounced around the globe once again, this time to do his Ph.D. in Scotland.

It was in Scotland that he first got the chance to roll up his sleeves and get hands-on with a rocket. The university was doing a few experiments on REXUS sounding rockets that involved a quick peek into the void — popping up 100 kilometers, then coming back down again, similar in concept to Spaceship 1 (the vehicle that Richard Branson funded that takes tourists up to space). It was there in Scotland that Thomas made “first contact” with a CYPRES cutter.

“We had these sounding rockets,” he remembers, “and we were searching for a way to release something from the rockets — some satellites we wanted to eject, for example. Most space hardware is very expensive, so you pay a couple thousand for just one release mechanism. Especially since we were students, that was not in the budget.”

A problem needs to be solved

To start to solve the problem, they talked the organisators of the REXUS programme, a consortium of the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) and the and the Swedish National Space Board (SNSB) together with the European Space Agency (ESA).

“For their sounding rockets,” Thomas says, “they were doing all the actuations with CYPRES cutters, and they had had a good experience with them. So we students got some expired ones from the Internet. We put them in and they always worked! So we used them on all of our sounding rockets.”

It was some time after Scotland that Thomas first joined forces with HPS GmbH, the organization where he now

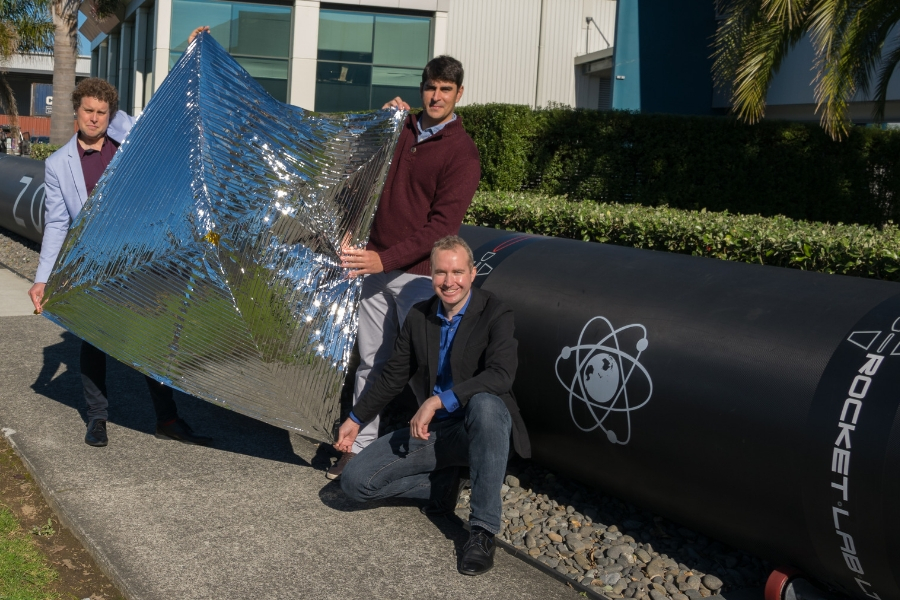

works. At HPS, he’s helping to solve a very pressing problem in a very interesting way. HPS is developing a dragsail subsystem that’s used to remove space debris. HPS has teamed up with Rocket Lab USA (motto: “Opening Access to Space to Improve Life on Earth”), to help get those space-scrubbing dragsails up where they can do their jobs, as well as helping HPS to push that dragsail development even further.

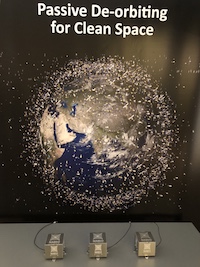

Why? Because space junk looms as one of the most important (albeit rather hidden) environmental efforts of our time. NASA tracks more than 500,000 pieces of debris — dead satellites and other bits of detritus — as they orbit the Earth.

Right now, the situation is quite lawless. The only standard that pretends to exist is a 25-year guideline that says the following: if you launch something into space, you have to make sure that, within 25 years, it is able to remove itself from orbit. It’s not binding. If you fulfill it, great; if you don’t, it’s not a really big deal yet. Nobody will come after you.

A new trend in space flight

“The trend in space flight right now is different than it was,” he explains. “We went from very big satellites — from two to four tons — to a lot of really small ones — one or two kilograms. The small ones you can build rather quickly and cheaply, so universities or startups can use them very well. There is a standard size which is a box of 10 by 10 by 10 centimeters, and with this standard, it makes all the integration and the launch very cheap. Now with the rise of mega constellations like One Web, with a few hundreds of satellites, a lot of them get made, and a lot of them get launched, and the situation just keeps getting worse and worse.”

So far, all the big space agencies follow the guideline, but many emerging countries and companies don’t. They insist

that they shouldn’t be burdened with the worry about space debris removal, arguing that most of the space debris was brought up there by America and Russia, so they should also have a matching 40 to 50-year “grace period” to making trash before considering removal.

“The idea behind these small satellites is that they’re disposable,” Thomas explains. “They are so cheap to build now, if a couple of them break, it’s not a big deal because you can just launch more — so you just let them break and leave them up there. That populates near space — especially the lower earth orbits, below 800 kilometers — with trash.”

That trash all travels at speeds up to 17,500 mph. And if the junkyard keeps growing unchecked? Bye-bye, outer space.

This is when the CYPRES cutters came into play

“In one point, space flight simply wouldn’t be be possible anymore,” he warns, “especially if you have collisions between those satellites, and you have a lot of additional small parts out there. With big parts, you can still move around them, but the small parts that you can’t see will destroy your spacecraft. Even now, every once in a while the International Space Station (ISS) needs to move out of the way of a piece of space debris flying by, and it’s only getting worse.”

HPS GmbH is now working (with the European Space Agency and the Clean Space Team) on systems to rid our orbit of such dangerous bits of flotsam and jetsam. They came up with the concept of using a dragsails to deorbit satellites when its usefulness is done. The sail is attached to a satellite before it launches; at the end of the mission life, it will open, increasing the drag area so it slowly spirals in and burns up in the atmosphere. Over time, that technology would slowly “scrub” low-earth orbit of space junk, resulting — hopefully — in a reasonably junk-free zone around the Earth, clearing the way for space missions. This is when the CYPRES cutters, thanks to Thomas’s student work in Scotland, came right back into play.

What were the requirements?

“When we got to designing the drag sail, [the CYPRES cutters] came back into my mind,” he says. “I contacted CYPRES and said that we were interested in using it for that application. They gave us some other references on other missions where it was used before. Then we put them in and we tested them, and they were the perfect thing.”

“The main requirement we had was that it works in a vacuum,” he continues. “Then, it had to be small. Also, the temperature range they must work in is also quite big — going down to minus 20 and 30 — but we didn’t know the exact temperature range. CYPRES just sent us a sheet that showed the ranges under which the cutter has been tested, and from that we made an assessment that it should work. The other thing that’s important is that the actuation is not very complex– It is just one single thing. You just have to apply the power and then it cuts. The criteria were pretty steep, but CYPRES fit them all.”

The final criteria, of course, is the same criteria that you and I use when we’re choosing an AAD: Reliability.

“I think about it being a lifesaving device in a parachute,” Thomas muses. “That gives us even more confidence that it will work every time. If it doesn’t cut, then we don’t deploy our structure in space. The stakes are high.”

The dream to chase

High-stakes space missions, of course, remain the dream to chase. Right now, RocketLab itself is launching something on the order one rocket per month; soon, they want to step that up to are also a bimonthly schedule, then weekly. The launch site, 1,000 kilometers away from Auckland on a New Zealand peninsula, presents a spectacularly beautiful place to locate a basis for scientific boundary-expansion.

“RocketLab is almost completely privately funded,” Thomas elucidates. “They are developing these very affordable rockets and launching them from New Zealand. The first rocket was named ‘It’s a Test.’ The second one was ‘Still Testing.’ We were very happy to be on their first business mission, which was called ‘It’s Business Time’ [a very funny reference to a song by the legendary Kiwi musical duo Flight of the Conchords.]”

“New Zealand realizes that space is where we should go next, for science and for business,” Thomas says, “And so they were supporting RocketLab. Also, all the universities are there are getting more and more into space. It is a very nice vibe there right now. It is an amazing country, and the people are great.” He adds that the next launch will be around April. You’re invited to watch!

Until then, Thomas will continue to fly the CYPRES flag as he builds sail after beautiful sail and flies them into space. We’ll be cheering him on every step of the way.

“Communication has always been very good with CYPRES,” Thomas smiles. “We enjoy very much working with them — not only because they are generous with their cutters for our testing process, but that the technical support is really good. Right now, we’re looking into longer-term space viability of these cutters, because the idea of these drag sails is that they’re deployed 5 or 10 years after the launch. We are looking forward to a future collaboration.”

So are we, Thomas!

To keep up with NABEO (and HPS’s and RocketLab’s other gorgeous efforts) or to simply gaze upon their knockout of a launch site, check them out on Twitter and Facebook. And support the project here, on Kickstarter!

Tags: CYPRES Cutter, Nabeo, space cutter, technology

Adventure, Tips, and Adrenaline

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

By signing up for our newsletter you declare to agree with our privacy policy.