Artifacts

Monday, December 29, 2025

- Joel Strickland

- 12/29/25

- 0

- General

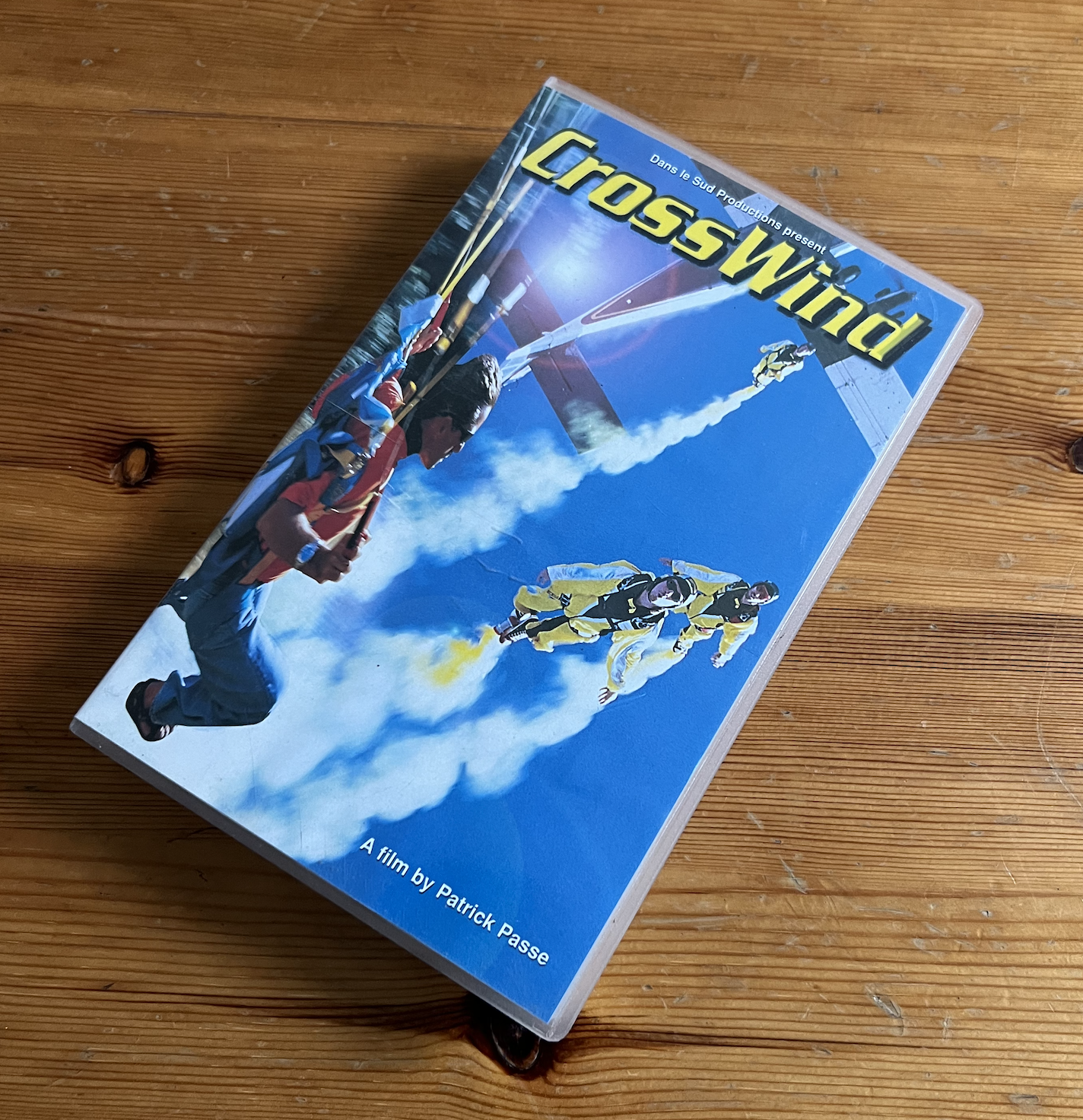

In one of the classrooms at Empuriabrava is a VHS copy of the skydiving film Crosswind – an hour-long documentary from 2001 produced and directed by Patrick Passe, and made with the involvement of many others. The room itself could be on a dropzone anywhere, as inside are familiar things – an aerial photo now old enough that more than a few things outside have changed, a scruffy whiteboard with some stickers around the edge, and a debrief station made from a basic screen plus a computer nobody needs for anything else. As there are other teaching spaces better equipped and more favoured, I have never once witnessed anyone use this room.

If you have not seen it, you can watch Crosswind online with ease, and you should, because time has been kind to a key text for what modern skydiving has become. It is like a blueprint for the future, a retro Rosetta Stone to translate and perceive new ways of thinking and flying. It rips. There is no VHS system in this room though, and even a dusty DVD player is tucked away in a corner, now also obsolete. Yet this videotape of Crosswind remains. Twenty-five years later, on a day-to-day basis at Empuriabrava you can still jump with, and learn from, people actually in the film – but I don’t think you could find anyone who would lay claim to owning that actual video copy. All other media has long since been removed, there are no other tapes, no discs, no pile of magazines. There is just an empty classroom containing a single item that has somehow gathered to itself enough power to remain there, seemingly for always. It serves no practical function, yet no-one has the need or the desire to remove it. It belongs to nobody and everybody. The item, once diminished by format and technology, via progression and perspective, has become something else.

Claude’s Things

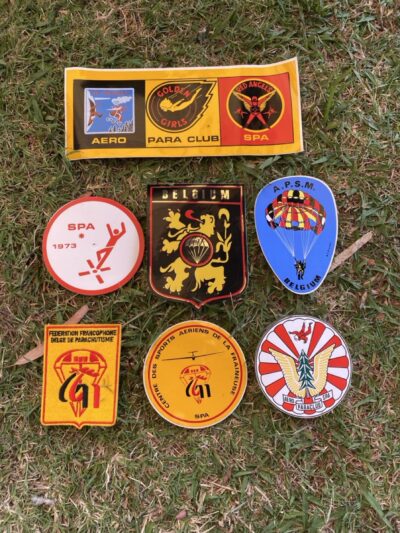

In early 2023 we were on tour in Australia, and I was mooching about at Ramblers for something to add to our little pile of gifts to take home for friends and colleagues. This started with campaigning for one of three vintage Australian Parachute Federation patches (excellent ones with kangaroos on them) kept on display behind the manifest desk, and ended with cataloging and archiving boxes of industry paraphernalia that went back through decades.

This turned out to be the personal archive of Claude Gillard, who had died a few years previously and been a legend of the sport – having started jumping in 1959 and then been involved at the highest levels of parachuting until his death in 2020 at 92 years old. An entire life of connections and experiences, from the all around the world and across many eras skydiving, represented in stickers, patches, and bits and bobs, carefully collected and squirreled away. Contained within are amazing pieces of history, a trail of breadcrumbs returning to the very origins of using parachutes for sport, some I which I wonder are events and gatherings now entirely lost to time and memory – save for these personal keepsakes spread out on the grass on a quiet, sunny day in Queensland.

The Choices

I enjoy wandering around the nooks and crannies of old skydiving clubhouses, and always take a little time to ask about the things that made it up onto the walls. It helps to grease the wheels of my professional role in the industry – representing a company with its own important history – but it is also fun and insightful because the stories can represent the entire spectrum of our experience. Skydiving culture is built upon the told tales of being in the right place at the right time, and the wrong place at the wrong time, and the lessons leaned from those that burn the brightest and have the most to share stand the test of time.

At Skydive Mimizan, down on the Atlantic coast of France, is my favourite old photograph from any wall of any club. There is a lot (so much) going on to spend time examining, but when I look at it my first and last thought is always the number of people in the picture that possibly consider that particular moment of collective experience among the best of their entire lives.

Once each year I return to Empuriabrava, and the first time I enter that classroom to store a few things for the night, I am always compelled to pick up and hold that video of Crosswind for a few seconds. I like the weight, the feel of the plastic case, and the particular rattle of a format that I am old enough to remember using, but it is also the sensation of enough time having passed to prove out the value of a thing. It is like the crackle of old Beatles 45s or the texture and smell of science fiction paperbacks – once long enough has passed, the medium of delivery serves to enhance the message itself.

Most of all, it feels like that moment of investing a lot of hours dissecting the narrative and exploring the map of some computer game, then way down deep, you find a hidden cave, and inside is a magic sword.

The way we share our stories may change, but the stories that matter the most find a way to stick around.

Adventure, Tips, and Adrenaline

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

By signing up for our newsletter you declare to agree with our privacy policy.